The unreliable narrator is one of my favorite literary devises. I also apply it to the adventures I GM and write. Here's why.

Misdirection in an adventure or series of adventures can add

a lot of fun to an adventure. Many times

it is assumed that the person inviting the group to adventure is honest with

the situation and intentions. When the

party is presented with situations such as a young boy being sacrificed or a

village is stricken with a plague, the extreme nature of the situation leaves

little doubt that helping is a good thing.

The nature of the narrator is not called into question because of the

situation. Even if he is a no good

bastard something needs to be done.

But the narrator is omitting information. Information that seems irreverent because of

the dire situation. Action is called

for. Adventurers excel at action. Adventurers are much like sharks, creatures

of motion and cease to exist when that movement stops. So when the call for action is made,

adventurers move. This unreliable

narrator relies on this trait, as should adventure designers. Using the traits of adventurers (and your

players) is to your advantage when developing a plot for your group.

In my recent adventure, Grim Water Oasis, the situation

presented is a young boy being sacrificed.

Not much gray area. Seems a

fairly straight forward reason to go kick some ass. However, the situation gets more complex if

the adventurers look deeper. The

sacrifice is made to feed the water spirit that feeds the oasis. The oasis provides life for a tribe of desert

people and the wildlife in the area. If

the adventurers go in crack’n skulls they have killed off dozens of more

people, children and much of the wildlife.

In the other situation where a village is stricken with a

plague, the bearer of the news pleads with the party to save them all.

There is a cure.

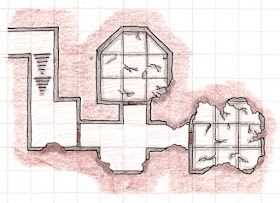

In my adventure, The Malice House, the cure

is with a hag that lives just over the boundary of hell.

She deals the adventuring party.

She will provide a cure if the party can

collect on a debt owed to her.

This time

the narrator is naïve of the situation behind the disease.

While saving the village is a good thing, the

party must make a deal with a creature of pure evil.

The same creature that created the disease.

Unreliable narrators, as I’ve given in the two examples, can

be by choice or by ignorance. Either way,

it is an adventure element of discovery.

Unveiling the truth after the fact or during the adventure. It puts the party’s ability to improvise to

the test. It adds depth to a simple

situation and leaves the door option for further development of adventures.

There is of course a danger if overused. The last thing you want to is make each

potential adventure hook rife with deception.

A little goes a long way. You can

tell when your party has reached the point of saturation, they get a case of paralysis by analysis. Or just call

every needy villager or tavern patron a big fat liar.

Next time your writing an adventure or setting the hook in

those adventurers mouth, add a little unreliability to the narrator. Your players will thank you. That last statement was brought to you by

your friendly unreliable narrator.